The Difference Between Morphine and Heroin

What Are Morphine and Heroin Made of?

Morphine is extracted from the seed pod of the Asian opium poppy plant and is a potent analgesic. Today it is manufactured by a host of pharmaceutical companies around the world and marketed under various names.

Heroin (or “diamorphine”) has up to 3 times the potency of morphine and is made by combining morphine – or opium, in the case of unlawful preparations – with a chemical reagent called acetic anhydride.1

What Do These Drugs Look Like and How Are They Administered?

Morphine in powder or pill form is typically a whitish-color. It can be injected below the skin, into muscle tissue, administered intravenously, used as a suppository or taken in pill form in various doses for opioid-tolerant patients.

Pure heroin is a white powder and mostly enters the U.S. from Central and South America. Heroin is usually sold as a white or brown powder that is typically cut with sugars, starch, powdered milk, quinine and possibly other impure additives. Heroin is frequently dissolved in a water solution and injected. Additionally, it may also be snorted or heated, with the resulting vapor being smoked or inhaled.

“Black tar” heroin looks like coal or roofing tar. Its black color is a result of impurities arising from the methods used to process it. This sticky form of heroin is most commonly consumed via needle-administered routes – injecting into veins, muscles or under the skin.2

What Are Morphine and Heroin Used for?

In the United States, morphine is categorized as a “Schedule 2 Drug” by the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). This drug category means that while morphine has accepted uses for medical treatment, its use is severely restricted, as it has a high potential for leading to strong psychological or physical dependence.

Morphine is an opioid that has been used as an analgesic to relieve pain for over 100 years. It is often used, for example, before and after surgery to reduce severe pain. And in the case of patients with HIV/AIDS, morphine is often prized as the “gold standard” to manage pain and improve end-of-life care.3

Heroin is extremely addictive no matter how it is administered. Its widespread use is identified as one of the most important drug abuse issues affecting several regions across the U.S.

Heroin, on the other hand, is categorized as an illegal, “Schedule 1 Drug” in the U.S. – meaning that it is currently not acceptable for any medical use.

Heroin lacks an acceptable safety level even under supervision of medical professionals, and it has a high potential for abuse.

How Do These Drugs Work in the Body?

Morphine and heroin work in the body in very similar ways – although they do also have their slight differences from each other.

Travel to the Brain

After absorption, morphine is mostly converted in the liver into two compounds (known as M6G and M3G). After absorption, morphine is rapidly and widely distributed and crosses the blood-brain barrier to enter the brain. Researchers have also found that a small amount of morphine is transformed to these compounds in the brain, itself. Both of these compounds can freely enter the brain.4

The way heroin works in the body is very interrelated with morphine. Similar to morphine, heroin can also freely enter the brain – only faster. Once in the brain, heroin is converted into morphine.

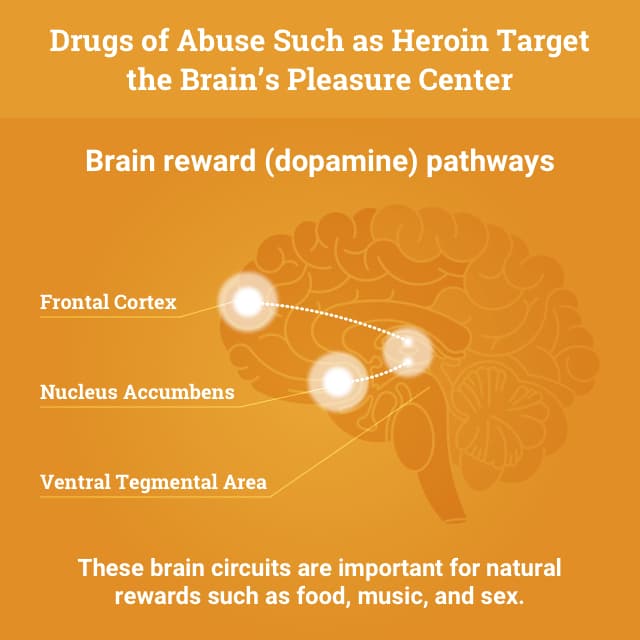

The Pleasure Chemical Dopamine Gets Activated by Opioid Receptors

Heroin and prescription opioid pain relievers such as morphine both belong to the opioid class of drugs. Their pleasurable, euphoric effects are produced when they bind with receptors called “mu opioid receptors” (MOR) in the brain.5

Receptors are specialized sites on body cells that chemical compounds attach to. Through chemical reactions, they send signals for certain activities to take place in the cell. Humans have chemicals that are naturally present in the body that also bind to mu opioid receptors. These receptors control release of certain hormones and are involved with modifying the perception of pain and general wellbeing. The activation of mu receptors causes release of dopamine, a naturally occurring chemical in the body related to sensations of pleasure.2

Such pleasurable feelings often reinforce the behavior that led to them – driving the user to repeat drug use. At some point, after a consistent period of regular use, users may find themselves continuing their drug use just to feel normal, and to stop or delay the onset of the extremely uncomfortable symptoms of withdrawal.

Short-term Effects of Morphine and Heroin

Heroin abusers often report feeling an initial pleasurable sensation – often called a “rush.” The intensity of this feeling depends on how much of the drug is taken and how quickly the drug enters to the brain and binds to the MORs.

Some who’ve used morphine have reported feeling a “rush” from morphine that is similar in nature to that of heroin – only weaker and with a slower onset compared to heroin.

A heroin rush typically includes the following sensations and symptoms:

- A warm feeling traveling through the skin and body.

- A feeling of heaviness in arms and legs.

- Dry mouth.

- Possible nausea and vomiting.

- Itchiness.

Soon after the rush, users may also experience:

- Drowsiness.

- Clouded mental functioning or dizziness.

- Slowed heart functioning.

- Slowed breathing – which can lead to coma and damage to the brain.2

Long-term Effects of Morphine and Heroin

Long-term effects on the body from using heroin and morphine are essentially one and the same. Both drugs are opioids, and – as mentioned earlier – heroin is not only derived from morphine but is also converted into morphine in the brain.

Morphine’s Long-term Effects – a Rare Bird?

The long-term effects of morphine may be a bit more unusual to find among users in the general population than those of heroin, as morphine is only accessible and distributed through medical professionals. Its potency is generally 3 times weaker than that of heroin.

Also, since heroin is produced “on the street,” it tends to be cut with a number of unpredictable impurities that can add to the harmful bodily effects we more commonly see with long-term heroin use.

Long term use of heroin has been found to change the physical structure and physiology of the brain, creating long-term imbalances in neuronal and hormonal systems that are difficult to reverse.2 Studies show some deterioration of white matter in the brain – a deterioration which can result in6:

- Decreased ability to make decisions.

- Decreased ability to monitor one’s own behavior.

- Poor ability to respond to stress.

In addition to the deterioration of the brain’s white matter, long-term effects of opioid use can also include:

- Insomnia.

- Chronic constipation.

- Sexual dysfunction (both men and women).

- Irregular menstrual cycles or spontaneous abortion (women).

- Lung complications.

- Heart lining and valve infections.

- Addiction and tolerance.

- Kidney diseases – nephrotic syndrome, acute glomerulonephritis, interstitial nephritis, renal amyloidosis and renal pathology.

- Physical damage as a result of snorting, smoking or injecting the drug – such as injection risks of acquiring a deadly infectious disease (HIV or hepatitis) as a result of sharing needles.

- Overdose and death.7

The minimum fatal dose of morphine or diamorphine (heroin) in an adult who is not used to taking these compounds is estimated at 100-200 mg but may fluctuate depending on individual metabolism and bodyweight.8

Dependence and Withdrawal

Correctly managed under medical supervision, short-term use of morphine rarely causes addiction. Nonetheless, both morphine and heroin still have the potential to cause addiction as the body builds physical dependence.

Opiate Withdrawal Symptoms

Opioid withdrawal symptoms occur when morphine or heroin use is suddenly stopped. Withdrawal symptoms can start even in as few as 6 hours after last opioid use. They tend to peak between 24-48 hours after last use but can persist for weeks or months, depending on the user’s personal characteristics, drug history and method of drug detox.2

Typical opioid withdrawal symptoms include the following:

- Intense drug cravings.

- Depression, withdrawal fears, anxiety.

- Sweating, watery eyes, runny nose.

- Restlessness, insomnia, yawning.

- Diarrhea.

- Fever and chills.

- Muscle spasms, tremor, joint pain.

- Stomach cramps.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Elevated heart rate and blood pressure.9

Physical dependence is a normal adaptation by the body to regular exposure to a drug. Dependence is different than addiction, however, which is characterized by compulsive drug-seeking and drug use even in the face of very hazardous outcomes. Individuals who are physically dependent on opioid medications will experience withdrawal if they suddenly stop using the medication, but this process can be managed medically.

Get Help for an Addiction

If you or your loved one is struggling with addiction to heroin or morphine, please know that there are a number of options available to help you along the best recovery path for you. Call to speak with one of our recovery advisors who can help you learn about your possible next steps.

Sources

- World Health Organization, 1995. WHO | Basic Analytical Toxicology. Accessed 9 December 2015.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1997. Heroin. Web. Accessed 10 December 2015.

- Access to buprenorphine, methadone and oral morphine. World Health Organization. Accessed 16 December 2015.

- De Gregori, S. et al., 2012. Morphine metabolism, transport and brain disposition. Metabolic brain disease, 27(1), pp.1–5. Web. Accessed 17 December 2015.

- [5]. National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2015. Prescription Opioids and Heroin.

- What are the long-term effects of heroin use. National Institute on Drug Abuse.Web. Accessed 23 November 2015.

- What are the medical complications of heroin use? National Institute on Drug Abuse.

- Basic Analytical Toxicology. World Health Organization. Web. Accessed 30 December 2015.

- Kosten TR, O’Connor PG. Management of drug and alcohol withdrawal. New England Journal of Medicine 2003;348:1786-1795.

Heroin Rehabilitation Directory

Select a state to learn more about your treatment options.- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District Of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming

Help for Heroin Addiction

Do you know someone suffering from heroin addiction? Help is available. To find out more, please choose the selection that applies to you or the person suffering from addiction:

Fill out the form below to be contacted.

Repair the damage and start fresh today!